The octopus holds in its embrace the entirety of Gabija Grušaitė’s The Mycelium Dream. True, it exists on the visual plane of the book, staying to some extent in the shadows. The lights here are directed elsewhere – to the text. We therefore initially catch the octopus just out of the corner of our eye and immediately forget it. Just as we forget people who aren’t like us. We don’t notice what isn’t on our usual horizon, what we don’t know, what we cannot or do not want to make a direct and meaningful connection with.

And yet, the octopus is definitely here – everywhere. Or rather, she, the female octopus. Her tiny but clear black silhouette is nestled in the blue cover, which recalls the rippling of the ocean on a cloudy day. Her eight tentacles, like thick seaweed, like long strands of hair trailing in the water, envelop the novel both on the book’s first and last pages, and in a specially designed bookmark Moreover, the silhouette that appears on the cover is repeated to mark each chapter of the book. Even if the octopus is not to be found in the novel’s narrative – in the words arranged into sentences, paragraphs and chapters – she spills into the space outside the book, marking Grušaitė’s new creative direction.

Close your eyes.

The octopus is a mollusc with eight limbs and no shell. There are about 300 known species. Together with squid, cuttlefish and nautiloids, they fall within the class Cephalopoda. Viewed from a human perspective, these are very strange animals, with an extremely plastic and flexible bodies; limbs studded with tentacles, with each limb having its own brain, and capable of functioning autonomously; and skin which can instantly change colour to mimic the sandy seabed or rocks. These animals have unique brains unlike any other animal we know of; they are also known to be highly intelligent creatures, capable of opening jars, finding exits to mazes and using tools. They are also thought to have a complex inner life.

In evolutionary terms, the common ancestor of humans and octopuses was probably some strange fish-like worm with two eyes and a mouth which lived hundreds of millions of years ago. ‘If we want to study the intelligence of aliens,’ observes Peter Godfrey-Smith, an Australian philosopher and writer who studies animal minds, ‘octopuses are the closest thing we have.’

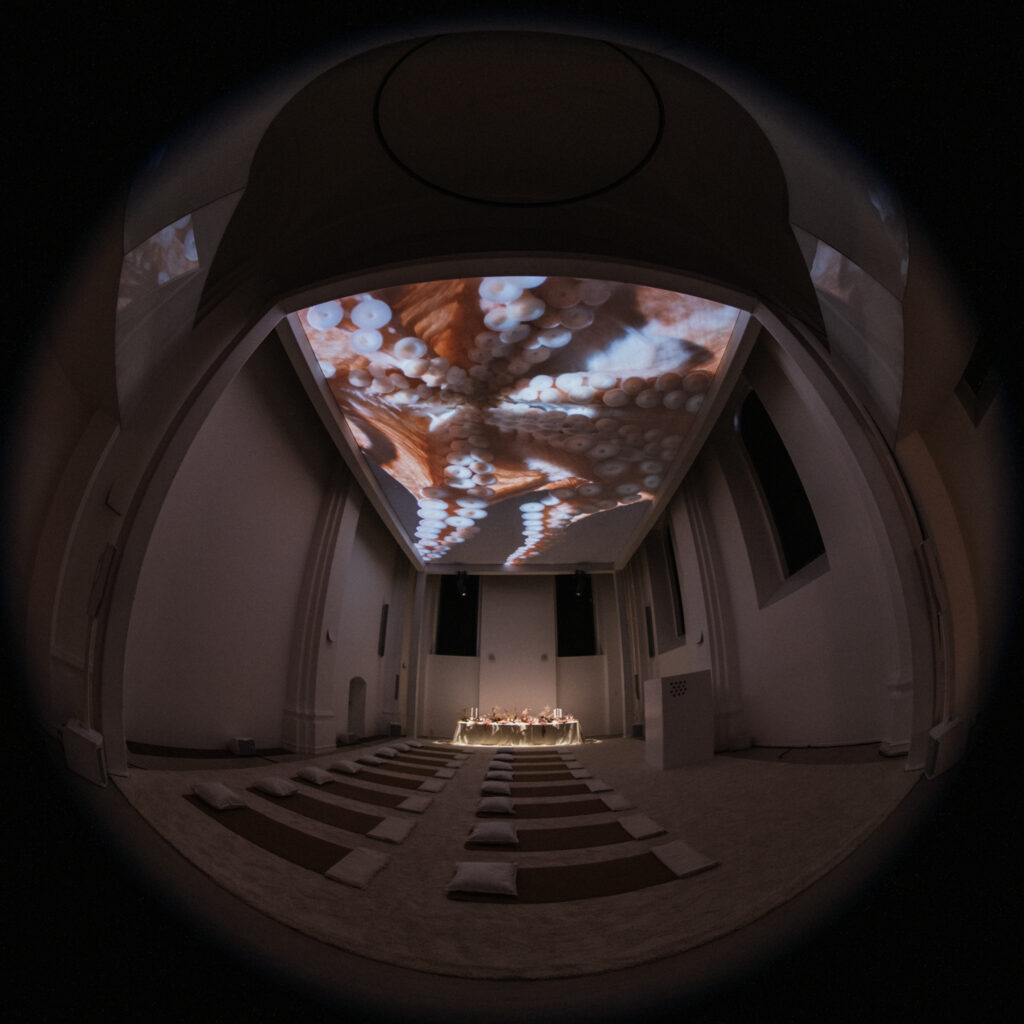

But Gabija’s installation doesn’t feature an octopus – that is, a female octopus – herself. There are only images of her: a hypnotic video which captures a cephalopod that lived in the aquarium of the Maritime Museum in Copenhagen, and eight plastic replicas of Octopus vulgaris dishes, which the artist ordered in various restaurants around the world. The dishes were her unusual way of grieving for her own deceased adopted octopus that had been caught for food in Spain and was later saved to spend the rest of her life in a captivity in Vilnius.

Her encounter with the octopus happened earlier, leaving a rippling trace in time, like in dark water, that encapsulates the multifaceted nature of human beings: gentle and cruel, caring and predatory.

Open your eyes.

In his legendary science fiction novel Soliaris, the Polish writer Stanisław Lem tells the story of a mysterious animal living on a distant planet – a vast ocean that defies human understanding. ‘We don’t need other worlds,’ he writes, ‘we need a mirror. We don’t know what to do with other worlds. This one is enough, we are already choking on it.’

Perhaps this date to which we are invited is not really with an octopus at all, but with ourselves. With all the unknown, autonomously operating parts of ourselves that live in dark waters. This installation, the date, is yet another chapter of Gabija Grušaitė’s book The Mycelium Dream, which once experienced will open a wider perspective on the artist’s work of literature and visual arts.

Neringa Bumblienė

Vilnius, 2024