KURATORINIS TEKSTAS

Tai – istorija apie tvirtovę, kurios valdos slypi Lietuvos kaimo glūdumoje. Jos gyventojai – daugiausia daiktai.

Medis, plienas, geležis, tinkas, marmuras, stiklas, keramika, akmuo, terakota, pigmentai ir kitos medžiagos diena po dienos gyvena gyvenimą didžiulėje industrinėje erdvėje, įsikūnydamos į milžinišką natiurmortą. Natūralaus dydžio natiurmortą, kuris, pertekęs gyvybės ar mirties, peržengia žmogiškojo mastelio ribas.

Tai Mariaus Grušo – menininko, išgarsėjusio Medeinės skulptūra – pasaulis. Jo skulptūra vaizduoja Medeinę – lietuvių miškų ir medžioklės deivę, išdidžiai sėdinčią ant meškos nugaros. Įkurdinta Vilniaus senamiesčio gatvėje, ji primena miestui, kad šis kadaise buvo miškas – ir vis dar yra.

Viskas yra miškas. Net ir Mariaus Grušo tvirtovė. O ši tvirtovė, kaip ir miškas, nepriklauso niekam. Jos neįmanoma suvaldyti, nes ji užvaldo, apsėda kiekvieną, peržengusį jos slenkstį. Tvirtovės šeimininkas yra imperijos, kurios jau nebėra, pavaldinys – arba baimės, kad imperija gali sugrįžti ir viską atimti, įkaitas. Tuo metu kiti šeimos nariai bando ištrūkti iš daiktų tironijos.

Šioje istorijoje nėra nei karaliaus, nei karalienės. Nėra princų ir princesių, laukiančių išgelbėjimo. O jei ir yra princesė – ji išsigelbės pati, su Medeinės stiprybe ir malone.

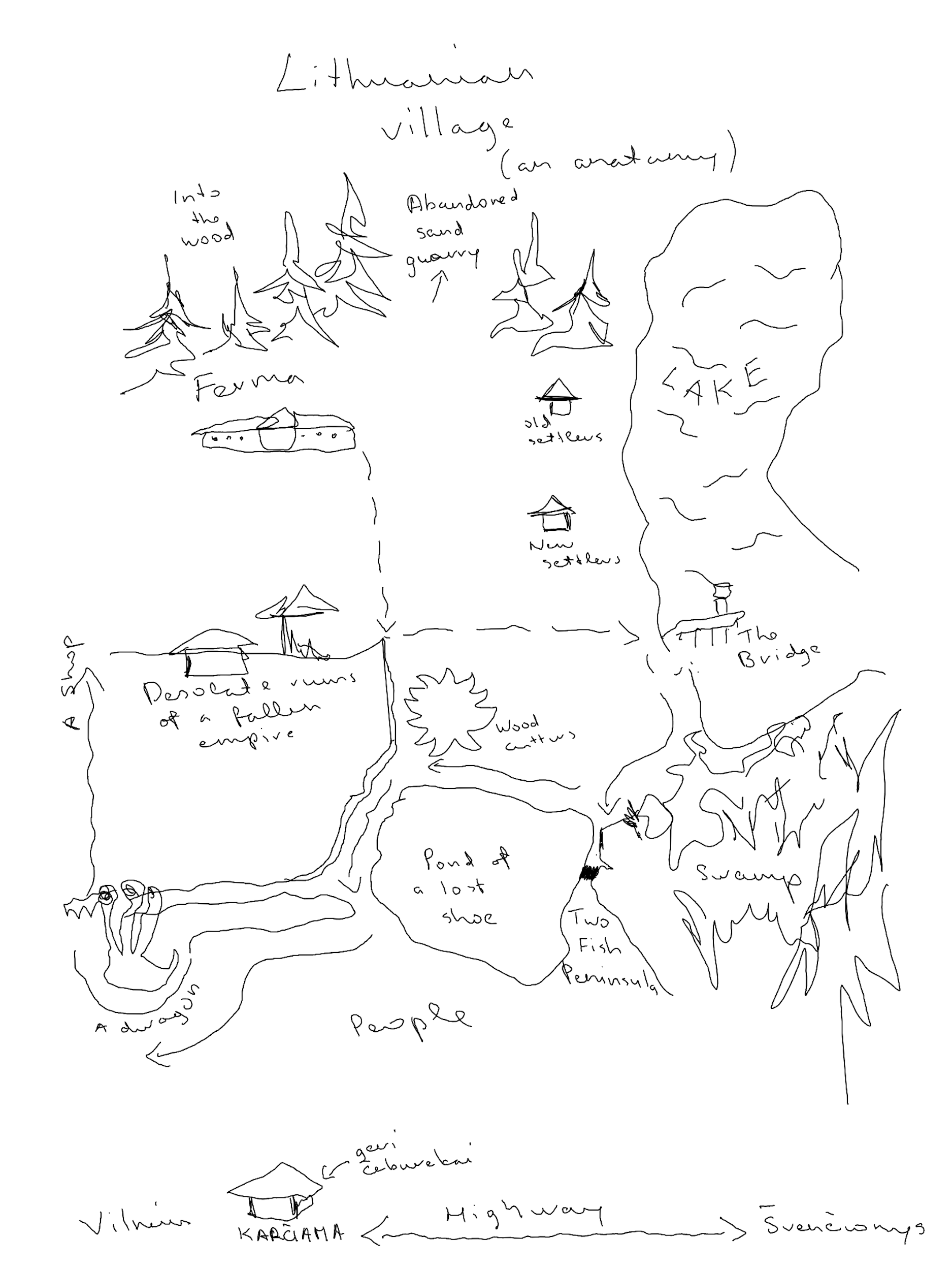

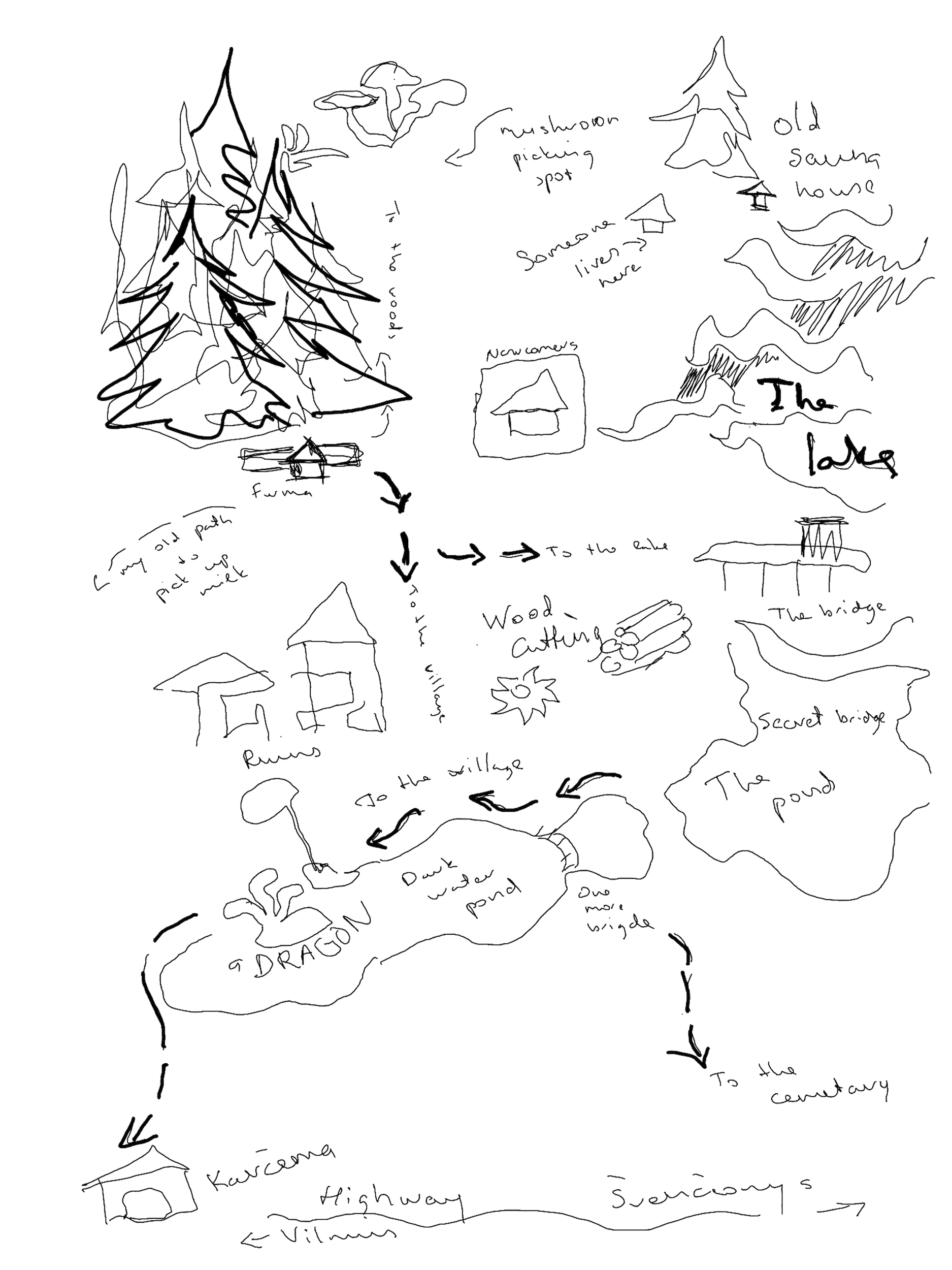

2025 metų rugpjūčio 7 dieną tvirtovės istorija prasideda iš naujo. Gabija Grušaitė grįžta į vietas, kurios paliko neišdildomą žymę jos vaikystėje, kad iš naujo perpaišytų asmeninį išgyvenimo žemėlapį ir pagaliau leistų jame apsigyventi kitiems.

Tirštam saugojimo ir sustingimo pojūčiui Grušaitė atsako horror pleni – pilnatvės siaubu. Jos žvilgsnis slysta per nesibaigiančio perviršio plyšius, ieškodamas perspektyvų ir pabėgimo krypčių, kurios anksčiau nebuvo prieinamos.

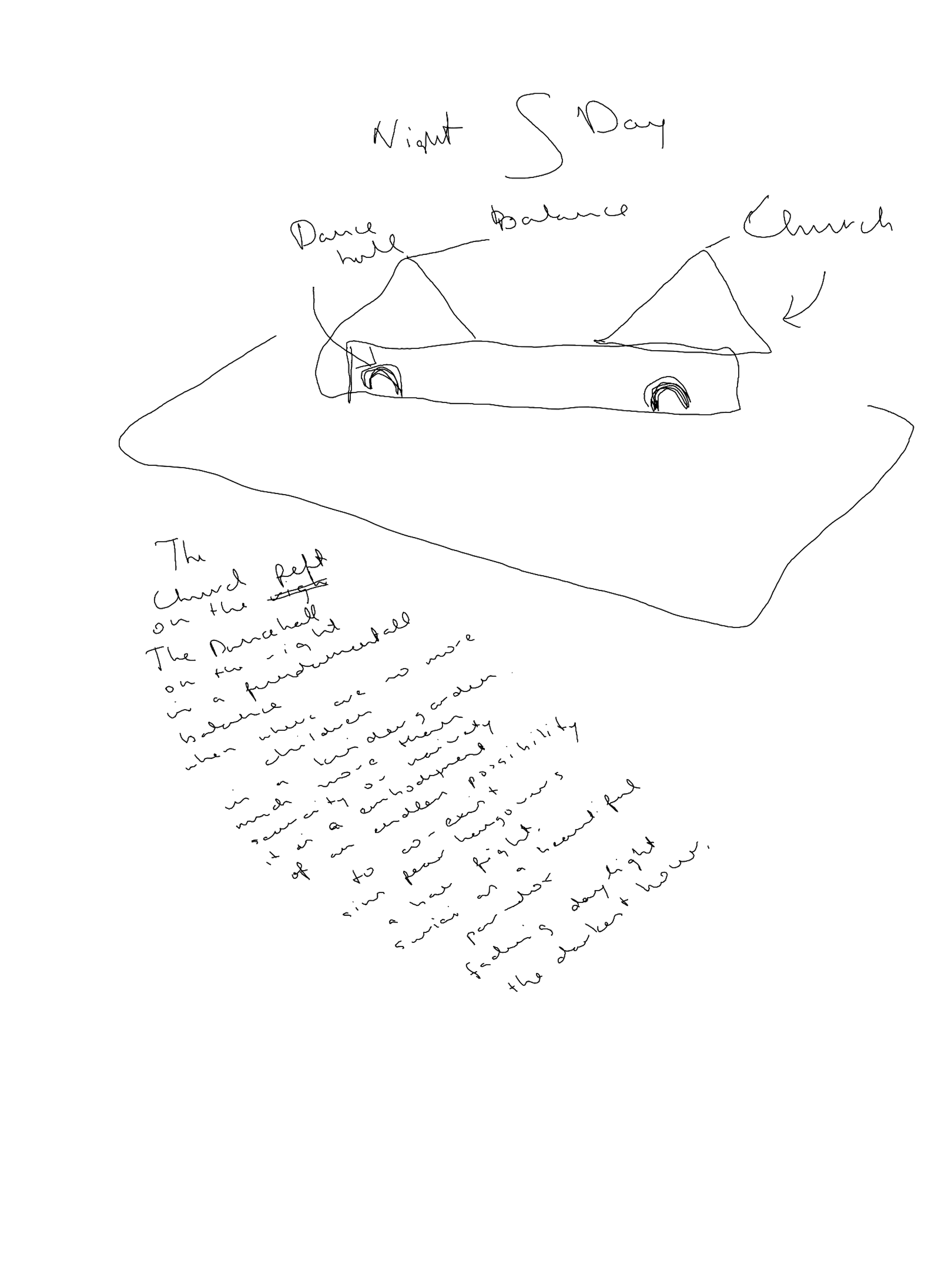

Žodžiai – menininkės pasirinkta terpė – šiame kūrinyje tampa naujo naratyvo audiniu, atskleidžiančiu ne tik jų pradinę kilmę, bet ir galimybę peržengti kalbos barjerą. Nors to galėtume tikėtis iš rašytojos, šį kartą G. Grušaitės tekstai neįgauna knygos teksto formos, o persipina su video kūriniais ir piešiniais, kurie žymi architektūrinę erdvę ir ją plečia.

Tarp daiktais perpildytų angaro eilių menininkė filmuoja kadrų seriją, jos balsas už kadro atkartoja erdvės fizinį ir emocinį tankį. Vaizdo įrašas rodomas veidrodiniu principu abiejuose angaro galuose, taip sukuriamas aidintis išsiplėtimo pojūtis: aidas ir tęstinumas, prasiskleidimas ir klaustrofobiškumas vienu metu.

Atskirame kambaryje – vienintelėje tuščioje viso komplekso erdvėje – menininkė eksponuoja žemėlapio piešinį: asmeninį orientacijos įrankį lankytojui.

Šis pasivaikščiojimas tampa iniciacijos ir išsilaisvinimo ritualu. Jis kerta Mariaus Grušo dirbtuvę, namus, fabriką, sandėlį – ir sujungia juos į vieną monumentalią meno kūrinio visumą, kuri peržengia pati save. Šis kūrinys – tarp paminklo ir griūvėsio, tarp realybės ir fikcijos, sąmonės ir pasąmonės, simptomo ir genialumo. Jis jau nepriklauso tėvui, bet dar nėra ir dukros.

Todėl, kad ši tvirtovė nėra asmeninė šeimos istorija. Daugiau nei tik intymi erdvė, savyje ji talpina ne tik vienos šeimos skausmą, bet atspindi visos postindustrinės, poagrarinės, posovietinės, pokapitaliptinės visuomenės, kuri nuolat atsiduria karo paribiuose, žaizdas.

Tai kvietimas į susitikimą. PTSD – potrauminio sindromo – susitikimas.